Hardback: Oxford UP, 2013

Buy now: [ Amazon ] [ Kindle ]

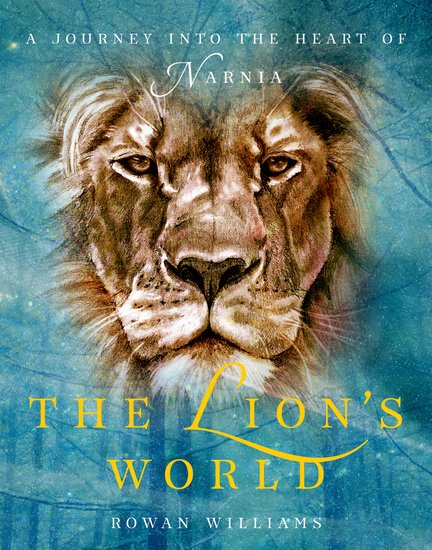

Recently, while discussing the role of fictional stories in spiritual formation with my students, I found myself returning to the works of C.S. Lewis as an example. While I did not discuss The Chronicles of Narnia, I can undeniably say that the fictional works of Lewis have shaped me spiritually. From a young age, I have read and reread the Narnian stories. They have become a part of my spiritual formation and of many others as well. Lewis has had this effect on Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury, as well. He also confesses to repeatedly reading and studying the Lewis’ works and writes of Lewis, “He is someone that you do not quickly come to the end of – as a complex personality and as a writer and thinker” (xi). In The Lion’s World, Williams explores this complexity of Lewis in conjunction with the depth of the Land of Narnia that Lewis created. He doesn’t set out to “decode images or to uncover a system;” instead he aims “to show how certain central themes hang together – a concern to do justice to the difference of God, the disturbing and exhilarating otherness of what we encounter in the life of faith” (6).

Williams begins by discussing Lewis’s intent for writing Narnia. Lewis realized that he lived in a culture that thought they knew what Christianity was all about and denied it, without actually knowing what they denied. He found that he was, “dealing with a public who thought they knew what it was they were disbelieving when they announced their disbelief in Christian doctrine” (17). It was a culture that believed they knew what they were against because it was a part of their culture. Because of this, Lewis wrote fiction to help his readers engage with religion without religious speak. “He wants his readers to experience what it is that religious (specifically Christian) talk is about, without resorting to religious talk as we usually meet it” (19). Lewis attempted to make world where we can encounter the Christian story in a strange new way, specifically a world aimed at children. This strange encounter with the Christian story is what Lewis called “mouthwash for the imagination.” Williams writes that, “The point of Narnia is to help us rinse out what is stale in our thinking about Christianity – which is almost everything” (28).

Chapter 2 is a brief look at the criticisms of Lewis’s work. The three main critiques of Lewis are racial stereotyping, sexism, and violence. In addressing the critiques, Williams both defends and accuses Lewis in his writing. Essentially, there are faults in Lewis, but if we faithfully read Lewis’ work, but he is certainly not one sided in these areas of criticism. While he portrays violence, he is certainly not unashamedly for it. While may show women in an old fashioned light, his stories are not without their strong women. While these things exist in his work, it is important to remember what culture Lewis came out of and see that in fact there are times when he is against those things of which he is accused. Williams sums it up like this, “In short, Lewis is indisputably a writer whose instinctive – and sometimes quite deliberate – attitudes to women and ethnic ‘others’ are abrasive for most contemporaries. But – as with any pre-modern writer – what is interesting is not how Lewis reflects the views of an era but how he qualifies or undercuts them in obedience to the demands of a narrative or a spiritual imperative or both” (45-46).

After the critiques, Williams moves on to a more in depth look at the lion himself. In The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Aslan comes the “rightful king of Narnia, but he makes his first appearance as a rebel against the established order” (50). He destroys the endless winter of the witch. Again, in Prince Caspian, Aslan is, in a more pronounced way, connected with conspiracy and revolt. Williams suggests Lewis, “is introducing us to a God who, so far from being the guarantor of the order that we see around us, is its deadly enemy” (50). This likely comes out of Lewis’s childhood. While growing up, Lewis was angry at God for making a world filled with suffering. In Narnia, however, Aslan is the one who delivers us from, “Tyranny and suffering and above all the dreary dictatorship of unthinking and bullying power” (51).

Not only does Lewis present this vision of God rebelling against the tyranny of the world, but meeting him always evokes great joy and pleasure. And while he is good and to be enjoyed, but it is never forgotten in Narnia that he is not a tame lion and one must accept him as he is. Lewis presents Aslan as being unashamed of who he is and impossible to change. “Aslan cannot make himself other than he is; he cannot make saltwater fresh, and if we elect to drink saltwater, he cannot make the consequences other than they are” (68).

Chapters 4 and 5 describe how personally interacting with Aslan affects someone. Aslan interacts redemptively with different individuals throughout the Narnian stories. The key to his interactions is how personal Aslan is and how he helps individuals see their part in the story and how Aslan is working in their life. Aslan does not want someone to be concerned with how he is working in another’s life, but wants to reveal how he is working in that person’s life. We each have a part in the story, and Aslan is giving the chance to make amends and fix our mistakes. It is very difficult for all those who are confronted by Aslan. Some who are confronted, like Lucy in Voyage of the Dawn Treader, are willing to repent. Others are choose not to accept the truth like the dwarfs in The Last Battle. Only in meeting Aslan, however, can the truth be revealed and understood.

In his final chapter, Williams explores the depths of Aslan’s country. At the end of the Chronicles of Narnia, the characters find themselves stepping out of Narnia and into Aslan’s country. A place that they can only described as a more real version of Narnia. It is a deeper and more vivid version of the world that we know. “Everything we know is a copy of ‘something in Aslan’s real world’, England no less than Narnia. So the further we go into Aslan’s world, the more vivid becomes our apprehension of what has mattered in our own world” (116-117). Lewis shows us that the end of all things does not end all things, but instead the beginning of the real reality. Death is not the end and neither is the end of the universe, instead it is beginning of real life in Aslan’s country.

Rowan Williams does an amazing job of exploring the depths of Narnia and unpacking the story the Lewis uses us to teach children and adults about the Christian story. In his conclusion, Williams rightly surmises, “The reader is brought to Narnia for a little in order to know Aslan better in this world” (144). There is so much more that could be said about this book, but if you love Narnia and want to explore the depths even more, I would highly encourage you to read this book. Although at times Williams speaks on an academic level about Narnia, the message of Rowan Williams’s The Lion’s World is clear and will benefit anyone who loves the Chronicles of Narnia. After reading The Lion’s World, I want to go and experience the world of Narnia all over again.